Americas 6000000 Shrine for All the Craziest Art

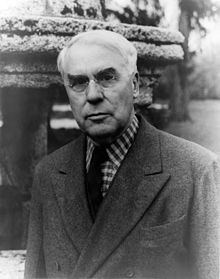

| Albert C. Barnes | |

|---|---|

Albert C. Barnes in 1940 | |

| Born | Albert Coombs Barnes (1872-01-02)January 2, 1872 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Us |

| Died | July 24, 1951(1951-07-24) (aged 79) virtually Malvern, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Alma mater | Academy of Pennsylvania |

| Known for | Businessman, art collector |

Albert Coombs Barnes (January 2, 1872 – July 24, 1951) was an American chemist, businessman, art collector, writer, and educator, and the founder of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1] [2] [3]

Early life and instruction [edit]

Albert Coombs Barnes was built-in in Philadelphia on January 2, 1872 to working-class parents. His begetter, butcher John J. Barnes, served in the American Civil War in Company D of the 82nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.[4] He lost his correct arm at the Boxing of Common cold Harbor.[2] : 38 After the state of war John Barnes received a disability pension of $8/month, and took jobs such as inspector, nighttime watchman,[5] and letter carrier when he could notice them.[4] Albert Barnes' female parent, Lydia A. Schaffer, was a devout Methodist who took him to African American campsite meetings and revivals.[1] The family lived first at 1466 Cook Street (now Wilt Street) in the rough working-class neighborhood of what is today Fishtown, and later in a slum surface area known as "the Neck" or "the Dumps".[4]

Albert Barnes completed uncomplicated schoolhouse at William Welsh Elementary School in 1885.[three] : 12 That yr Barnes was ane of two boys from his schoolhouse who were accepted at Central High School, a public school highly respected for its rigorous academic program.[5] [iii] : 12 Barnes graduated at age 17 on June 27, 1889 with an A.B. degree,[v] office of the 92nd form.[3] : 12 [vi] At Cardinal Barnes became friends with William Glackens, who later on became an artist and advised Barnes on his first collecting efforts.[vii]

Barnes went on to attend medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, enrolling in September 1889[3] : 13 and receiving his degree as of May 6, 1892.[eight] : 333 He earned his way by tutoring, boxing, and playing semi-professional baseball.[9] : 9 [5] In 1892, he interned at Polyclinic Hospital in Philadelphia[10] [8] : 345 and at the Mercy Hospital of Pittsburgh.[4] [11] He too is listed as having been an assistant physician at the State Hospital for the Insane in Warren, Pennsylvania in 1893.[12] His experience as an intern convinced him that he was non suited to clinical exercise.[3] : 13 Although he obtained the degree of medical doctor, he never practiced.[13] [three] : xiii

Barnes decided instead to pursue an interest in chemical science as it practical to the practice of medicine.[3] : 13 He traveled to Germany, so a center of chemical research and pedagogy, studying in Berlin effectually 1895. Returning to the United states of america, he joined the pharmaceutical company H. One thousand. Mulford in 1898. The company sent him dorsum to Federal republic of germany to study in Heidelberg,[5] a city that Barnes described as "a loadstone [sic] for scientific investigators of every country."[14] According to the Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie he was among those receiving firsts and seconds, given June 26, 1901, from the Pharmakologischen Institut zu Heidelberg.[xv]

Career [edit]

In 1899, he went into business with German chemist Hermann Hille (1871-1962), and created Argyrol, a silver nitrate antiseptic which was used in the treatment of ophthalmic infections and to prevent newborn babe incomprehension caused by gonorrhea.[16] The ii left H.K. Mulford and Company to organize a partnership called Barnes and Hille. This new company was founded in 1902. Hille ran production and Barnes ran sales. The company prospered financially, but the relationship between the two men waned. In 1908 the visitor was dissolved.[ane] Barnes went on to course A.C. Barnes Visitor and registered the trademark for Argyrol.[17] In July 1929 Zonite Corporation of New York bought A.C. Barnes Company. The motility was well timed as the stock market place crashed in Oct that year.

Marriage and family [edit]

Barnes married Laura Leggett (1875 - 1966), daughter of a successful grocer in Brooklyn, New York City, but had no children.[ane]

When the Barnes Foundation was established, Laura Barnes was appointed as vice president of the board of trustees. Following the death of Captain Joseph Lapsley Wilson, she became the director of the Arboretum. In October 1940, she began the Arboretum School of the Barnes Foundation with the Academy of Pennsylvania botanist John Milton Fogg Jr. She taught plant materials.[18] She regularly corresponded and exchanged plant specimens with other major institutions, such as the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

She succeeded her husband as president of the Foundation afterward his expiry in 1951. She died April 29, 1966, leaving her art collection to the Brooklyn Museum of Fine art.[eighteen]

Her work was recognized past the 1948 Schaffer Memorial Medal from the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. In 1955, she became an honorary fellow member of the American Society of Mural Architects. She received an honorary doctorate in horticultural science from St. Joseph's University of Philadelphia.[18]

Art collecting [edit]

In 1911, Barnes reconnected with his high school classmate William Glackens and in January 1912, just after turning 40 years old, Barnes sent him to Paris with $xx,000 to purchase paintings for him. Glackens returned with 33 works of art.[3] : 19

Following the success of Glackens' buying entrada, Barnes traveled to Paris twice himself, the same yr. In Dec, he met Gertrude and Leo Stein and purchased his first 2 Matisse paintings from them.[19] Barnes purchased his collection of African Fine art from art dealer Paul Guillaume (1891- 1934), who served briefly equally the Barnes Foundation's "foreign secretary."[xix]

The collection changed throughout Barnes' lifetime every bit he caused pieces, moved them from room to room, gifted pieces, and sold them. The art works in the Barnes Foundation reflect how they were hung and placed at the time of his death in 1951. There are over four,000 objects in the collection including over 900 paintings and well-nigh 900 pieces of wrought iron. Some major holdings include: 181 works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 69 works by Paul Cézanne, 59 works past Henri Matisse, 46 works by Pablo Picasso, and 7 paintings by Vincent Van Gogh. In 1923, Barnes Purchased Le Bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life), a painting once owned by Gertrude and Leo Stein, bought from Christian Tetzen-Lund through Paul Guillaume for 45,000 francs.[20] : 153 In 1927, he purchased Renoir's The Artist's Family from Claude Renoir through Galerie Barbazanges for $50,000.[21] The collection too includes many other paintings and works by leading European and American artists, besides as African art, art from China, Greece, and Native American peoples.

The Barnes Foundation [edit]

Barnes had a longtime interest in education; he held two hr long employee seminars at the finish of the day in his manufactory.[22] At the seminars, his primarily African American workforce would discuss philosophy, psychology, and aesthetics reading James, Dewey, and Santayana.[23] With friend and mentor John Dewey he decided to expand his educational venture. In December 1922, the Barnes Foundation received its charter from the state of Pennsylvania as an educational institution. He hired Franco-American architect Paul Philippe Cret to build a gallery building, residence (administration building), and service building. The gallery served as a instruction tool for students to study fine art using a method based on the scientific method. Barnes consulted with attorney Owen Roberts (1875-1955) when setting upwards the by-laws and the indenture.[iii] : 29 In 1925, the buildings were completed and the Barnes Foundation opened. The collection is not hung traditionally, instead they are arranged in "ensembles" which are organized following the formal principles of light, colour, line, and infinite. The focus of Barnes's teachings were on the fine art itself rather than its historic context, chronology, style, or genre. Barnes did not provide documentation on the significant of each system.

Operations [edit]

Since the Barnes Foundation was an educational institution, Barnes express access to the collection, and oft required people to make appointments by letter of the alphabet. He frequently declined visitors who wrote and asked to visit. He specially did not capeesh the wealthy and entitled requesting visits and would ofttimes rudely answer them. In 1939, Barnes sent a letter, posing equally a secretarial assistant, informing Walter Chrysler he could not visit because he (Barnes) "is non to be disturbed during his strenuous efforts to break the world's tape for gold-fish swallowing."[9] : xiii

Influenced past the Philadelphia Museum of Art's handling of the donated fine art collection of his late lawyer, John Graver Johnson, Barnes wanted to make his intentions clear in the Foundation's indenture and trust. It stated, "all paintings should remain in exactly the places they are at the fourth dimension of the death of Donor [Barnes] and his said wife."[24] From his death in 1951 the specific arrangement of the paintings and art remained the same until, at the asking of the Barnes Foundation, the Montgomery County Orphans' Court overruled the indenture in 2004.[25]

Litigation to open up the Barnes Foundation to the public began seven months after Barnes' expiry. In March 1961 information technology was opened to the public on Fridays and Saturdays, and then expanded to 3 days a calendar week in 1967, after Mrs. Barnes' expiry in '66, and remained that manner until the 1990s.[26] Barnes also had strong feelings against colour photographs of the collection as the quality was not upward to par with the then current technology. In regards to a request for color photographs Mrs. Barnes wrote to Henri Matisse: "Despite the improvement of the photographic procedure, information technology does not faithfully reproduce the verbal colors of the artist. And at that place is farther difficulty in making colour plates for a book."[20] : 282 The stance is often criticized. The critic Hilton Kramer wrote of Matisse's Le bonheur de vivre: "attributable to its long sequestration in the collection of the Barnes Foundation, which never permitted its reproduction in color, it is the to the lowest degree familiar of modern masterpieces. Withal this painting was Matisse'south own response to the hostility his work had met with in the Salon d'Automne of 1905."[27]

Relationship with art world [edit]

In 1923, a public showing of Barnes' collection at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts proved that information technology was besides avant-garde for most people'south taste at the time. Some headlines from the time are, "Academy Opens Notable Exhibit: Mod Art Bewilders"[28] and "America's $half dozen,000,000 Shrine For All the Craziest 'Fine art'."[29] The critics ridiculed the prove, prompting Barnes' long-lasting and well-publicized animosity toward those he considered role of the art establishment. For example, he said to Edith Powell, of the Philadelphia Public Ledger, that she would never be a real art critic until she had relations with the ice human.[30]

Barnes' interests included what came to exist chosen the Harlem Renaissance, and he followed its artists and writers. In March 1925, Barnes wrote an essay "Negro Art and America", published in the Survey Graphic of Harlem, which was edited by Alain Locke.[31] Barnes also continued to support young African America artists and musicians with scholarships to study at the Foundation. At the suggestion of Charles S. Johnson, he admitted artists Gwendolyn Bennett and Aaron Douglass as scholarship students in 1928. Douglas continued to illustrate books and pigment murals before leaving to study and piece of work in Paris. Barnes gave scholarships to singers James Boxwill and Florence Owens to written report at the Foundation, and besides provided funding for violinist David Auld to study at the Juilliard School, and for singer Lillian Grand. Hall to nourish the Westminster Choir College in New Jersey. In 1943, Barnes sent California musician Ablyne Lockhart into the Deep S to become acquainted with "her roots". Lockhart sent Barnes vivid descriptions of her trip which included transcriptions of the spirituals she heard while visiting St. Helena Island in Due south Carolina. Barnes's support of African Americans extended beyond the cultural disciplines. As early as 1917, Barnes helped his African American workers buy houses in Philadelphia. In the early 1930s, he provided a fellowship for Philadelphia physician DeHaven Hinkson to study gynecology in Paris. He as well paid for the education of Louis and Gladys Paring, the children of Jeannette Thou. Paring, widow of an A.C. Barnes Company employee, at the Manual Training and Industrial Schoolhouse for Youth in New Bailiwick of jersey, an example of his abiding delivery to his employees and their families."[1]

Publications [edit]

Barnes wrote several books about his theories of art aesthetics. He was assisted by his educational staff, whom he also encouraged to publish their ain writings. From 1925-26, he and the staff published articles in the Journal of the Barnes Foundation.[32]

- The Art in Painting (1925).[33]

- The French Primitives and Their Forms from Their Origin to the Terminate of the Fifteenth Century (1931), with Violette de Mazia (1899-1988). A native of Paris, at the fourth dimension she was a teacher at the Foundation; in 1950, Barnes appointed her every bit Director of Education.[34]

- The Art of Renoir (1935), with De Mazia.[35]

- The Art of Henri-Matisse (1933), with De Mazia.[36]

- The Art of Cézanne, with De Mazia.[37]

- Fine art and Pedagogy (1929-1939), with John Dewey, Lawrence Buermeyer, Thomas Mullen, and De Mazia. These were collected essays by Barnes, Dewey, and his educational staff, originally published in the Journal of the Barnes Foundation (1925-1926). (Barnes hired Buermeyer (1889-1970) and Mullen (1897-), former students of Dewey, each to serve as Assistant Director of Education for a time; Dewey was Director during this menstruation in what was essentially an honorary position.) [32]

Later on years [edit]

In 1940, Barnes and his wife Laura purchased an 18th-century manor in Westward Pikeland Township, Pennsylvania, and named it "Ker-Feal" (Breton for "House of Fidèle") after their favorite dog.[iii] : 45 Barnes requested art dealer Georges Keller prefer and bring the canis familiaris he met while vacationing in Brittany, France to Merion.[i]

In the belatedly 1940s, Barnes met Horace Mann Bail, the get-go blackness president of Lincoln Academy, a historically black higher in southern Chester County, Pennsylvania. They established a friendship that led to Barnes' inviting Lincoln students to the drove. In October 1950, he amended the by-laws of the indenture allotting seats on the Lath of Trustees to exist "...filled by election of persons nominated by Lincoln Academy..." also adding that "no trustee shall exist a member of the faculty or Board of Trustees or directors of the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, Bryn Mawr, Haverford or Swarthmore Colleges, or the Pennsylvania University of the fine Arts."[iii] : 49

Human relationship with Bertrand Russell [edit]

In the 1940s, Barnes helped salvage the career and life of the distinguished British philosopher Bertrand Russell. Russell was living in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the summer of 1940, short of money and unable to earn an income from journalism or teaching. Barnes, who had been rebuffed past the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Museum of Fine art, had been impressed past Russell's battles with the Establishment. He invited Russell to teach philosophy at his Foundation.

Russell invited Barnes to his motel in Lake Tahoe for discussion. He secured a contract to teach for v years at an annual salary of $half-dozen,000, subsequently raised to $8,000, and so Russell could give upwardly his other teaching duties.[3] : 45–46

The 2 men later cruel out after Barnes was offended by the behavior of Russell's wife Patricia, who insisted on calling herself 'Lady Russell'. Barnes wrote to Russell, saying "when we engaged you to teach we did not obligate ourselves to endure forever the trouble-making propensities of your wife",[38] : 262 and looked for excuses to dismiss him. In 1942, when Russell agreed to give weekly lectures at the Rand School of Social Science, Barnes dismissed him for breach of contract. He claimed that the additional $2,000 per year of his salary was provisional upon Russell'south teaching exclusively at the Foundation. Russell sued and was awarded $20,000— the amount owed being less than $four,000 and which the courtroom expected Russell to be able to earn from didactics in a 3-twelvemonth menstruum.[38] : 261–263

Expiry [edit]

Barnes died on July 24, 1951, in an car crash.[39] Driving from Ker-Feal to Merion with his canis familiaris Fidèle, he failed to stop at a end sign and was hit broadside past a truck at an intersection on Phoenixville Pike in Malvern. He was killed instantly. Fidèle was severely injured from the crash and was put down on the scene.[40] [one]

The Barnes Foundation in contempo decades [edit]

From 1990 to 1998, Richard Glanton served every bit President. During his term a choice of paintings were approved past the Montgomery County Orphans' Court to tour and heighten money for renovations. From 1993 to 1995, The Corking French Paintings from the Barnes Foundation: Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Early Modern exhibited. The paintings and other works attracted huge crowds in seven international cities.[41]

In 1998, Kimberly Camp became the get-go professional director in the history of the Barnes Foundation. When Camp arrived in the autumn of 1998, the Foundation had a $3.3 million deficit and was embroiled in numerous court cases. Under Camp'southward leadership, the arrears was eliminated, excepting a $one one thousand thousand structural deficit due to FASB changes. Camp led the Foundation's restoration of the arboretum in Merion and its second campus, Ker-feal, a 132-acre subcontract in Chester Springs. The Ker-feal restoration included a full inventory and mold remediation, funded in office past the W Pikeland Township. Camp restaffed the Foundation with professionals in their corresponding fields. The pedagogy program was returned to the methods used by Barnes during his lifetime. The retail division became for the first time, a profit middle. A licensing program was established allowing international utilise of images from the collection. Programs were established for regional G-12 schools, equally was intended by Barnes equally documented in his papers.

Camp'south work with her conservator, registrar, archivist and advisory commission created the Collection Assessment Projection, a multi-year, multi-million effort to catalog the collection, conduct conservation assessments and catalog archival records. With over 1,000,000 records, the Barnes archives is now public. It was Camp'due south research that provided the footing for the petition to relocate the Barnes Foundation to its center city location. Documentation provided in court proved, in Barnes' ain words, that the foundation could exist moved to Philadelphia. Camp remained at the Foundation through 2005 to ensure its shine transition to new leadership.

In 2002 the Foundation petitioned the Montgomery County Orphans' Courtroom for permission to expand its Lath of Trustees and move its gallery collection to Philadelphia and in December 2004 the court canonical the petition.[24] A new building designed by architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway opened on May nineteen, 2012. The move to Philadelphia was featured in the documentary picture show The Fine art of the Steal (2009).

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d east f m "Biographical Note," Albert C. Barnes Correspondence. The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2012. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids

- ^ a b Aichele, K. Porter (2016). Modern Art on Display: The Legacies of Half dozen Collectors. Newark, DE: Academy of Delaware Press. pp. 37–. ISBN978-1611496161 . Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d eastward f k h i j k l grand Wattenmaker, Richard J. (2010). American Painting and Works on Paper in The Barnes Foundation. Merion, PA; New Haven, CT: The Barnes Foundation in association with Yale University Press.

- ^ a b c d Meyers, Mary Ann (2006). Fine art, educational activity, & African-American civilisation : Albert Barnes and the science of philanthropy. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. ISBN978-1412805636 . Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Meyers, Mary Ann (2007). "Albert C. Barnes: Chemist, Entrepreneur, Philanthropist". Chemic Heritage Magazine. 25 (iv): 20.

- ^ Barnes, Albert C. (1937). "Art and the American Negro". The Barnwell Addresses. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Mary Gaston Barnwell Foundation. pp. 375–386.

- ^ Lewis, Susan (February 9, 2015). "The Creative person Who Launched Albert Barnes' Collection With A Trip To Paris and $xx,000". WRTI 90.1 . Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Catalogue and Announcements, 1892-93. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania. 1893.

- ^ a b Edouard, Lindsay (2011). "Antisepsis with Argyrol, Anger, and Advocacy for African Art". African Journal of Reproductive Health. xv (3): 9–14. JSTOR 41762341. PMID 22574488.

- ^ University of Pennsylvania Medical Bulletin: Volume I-XXIII. Oct, 1888 to Feb, 1911. Academy of Pennsylvania. School of Medicine.: Academy of Pennsylvania Printing. 1892. p. 737. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "He believes the story". Pittsburgh Acceleration from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. December 16, 1892. p. 2. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Warren State Hospital (1894). Annual Study of the Trustees of the Land Hospital for the Insane, Warren, Penn'a., for the yr ending Nov xxx, 1893 to the Board of Commissioners of Public Charities. Warren, Pennsylvania: E. Cowan & Company, printers. pp. 2, x. Retrieved Oct 5, 2017.

- ^ Leong, Jeanne. "For the Record: Albert Coombs Barnes". Penn Current. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Albert C (July 21, 1900). "Obituary: Professor Kuhne". Medical News. 77: 106. Retrieved Oct v, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Albert C. (1901). "V. Aus dem pharmakologischen Institut zu Heidelberg. Ueber einige krampferregende Morphinderivate und ihren Angriffspunkt". Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie. 46: three, four, 68–77. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Albert C.; Hille, Hermann Hille (1902). "A New Substitute for Silver Nitrate". Medical Tape: 814–815.

- ^ Declarations and Statements: Trade-Marks Registered in the United States Patent Function from June 2-nine-16-23 and 30th, 1908, vol. 127, function 169, 247-69, 499. Trademark registration no. 69,328.

- ^ a b c "Biographical Note," Laura Leggett Barnes papers, The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2012. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/drove/library-athenaeum/finding-aids

- ^ a b Judith F. Dolkart, "To Run across as the Artist Sees: Albert C. Barnes and the Experiment in Education," in The Barnes Foundation Masterworks, Judith F. Dolkart and Martha Lucy (Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2012), xi.

- ^ a b Bois, Yve-Alain; Butler, Karen K.; Grammont, Claudine; Buckley, Barbara (2015). Matisse in the Barnes Foundation. Vol. 3. Philadelphia, Pa.; New York ; London: Barnes Foundation : Thames & Hudson. ISBN9780500239414.

- ^ Martha Lucy and John House. Renoir in the Barnes Foundation. (New Haven and London: Yale Academy Press), 2012), 299.

- ^ Albert C. Barnes. "Dr. Barnes of Merion Tells His Story," radio address broadcast on station WCAU Philadelphia, April 9, 1942.

- ^ Laurence Buermeyer, "An Experiment in Education," The Nation 120, 3119 (April 1925): 422-423.

- ^ a b "Relocation of the Barnes Collection Fact Canvass" in the Philadelphia Opening Printing Kit, The Barnes Foundation, 2012 https://www.barnesfoundation.org/press/press-releases/movement-press-kit-2012

- ^ David D'Arcy, " 'Selling everything but the wallpaper' — auction reopens old wounds over Barnes legacy" The Arts Paper, 3rd June 2022 [1]

- ^ "Administrative History," Central File Correspondence. The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2006. https://s3.amazonaws.com/barnes-images-p-e1c3c83bd163b8df/assets/CFC_Pkwy.pdf

- ^ Hilton Kramer, "Reflections on Matisse," in The Triumph of Modernism: The Art World, 1985–2005, (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 162.

- ^ Academy Opens Notable Showroom: Modern Fine art Bewilders." Public Ledger, April 12, 1923. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045211/issues/.

- ^ "America's $6,000,000 Shrine For All the Craziest 'Art.'" Philadelphia Inquirer, April 29, 1923, 2.

- ^ Panero, James (July 1, 2011). "Outsmarting Albert Barnes". Philanthropy . Retrieved April eight, 2019.

- ^ Albert C. Barnes, "Negro Art and America", Survey Graphic, March 1925, accessed March 19, 2010

- ^ a b "Historical Notation," Art and Didactics manuscripts, Barnes Foundation Archives, 2006, https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Notation," The Art in Painting manuscript, The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2006, https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Note," The French Primitives and Their Forms manuscript, Barnes Foundation Archives, 2006, https://world wide web.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-athenaeum/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Note," The Art of Renoir manuscript, The Barnes Foundation Athenaeum, 2006, https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Note," The Art of Henri-Matisse manuscripts, Barnes Foundation Archives, 2006, https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Note," The Art of Cezanne manuscript, The Barnes Foundation Athenaeum, 2007, https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-athenaeum/finding-aids.

- ^ a b Monk, Ray (2001). Bertrand Russell : the ghost of madness, 1921-1970 . New York, NY: Complimentary Press.

- ^ "Dr. Albert Barnes Dies in Crash; Art Collector Discovered Argyrol." New York Times, July 24, 1951.

- ^ "Dr. Barnes Killed in Car Crash; Put Millions Into Mod Fine art." Herald Tribune, July 24, 1951.

- ^ "Great French Paintings from the Barnes Foundation: Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Early Modernistic, May ii, 1993- October 22, 1995," The Barnes Foundation. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/peachy-french-paintings#

Further reading [edit]

- Hart, Henry. Dr. Barnes of Merion: An Appreciation. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Company, 1963.

- Wattenmaker, Richard. American Paintings and Works on Paper in the Barnes Foundation. Merion: The Barnes Foundation; New Haven: in association with Yale University Press, 2010.

- Dolkart, Judith and Martha Lucy. Masterworks: The Barnes Foundation. New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications Inc., 2012.

- House & Garden, December 1942 vol. 82, no. 6.

- Barnes and Beyond. Dir. Art Fennell. Fennell Media, 2014. DVD.

- The Barnes Collection. Dir. Glenn Holsten. PBS, 2012. DVD.

- The Collector: An investigation of the brilliant, passionate, and sometimes hard personality behind the Barnes collection. Dir. Jeff Folmsbee. HBO, 2010. DVD.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_C._Barnes

0 Response to "Americas 6000000 Shrine for All the Craziest Art"

Post a Comment